Forty-five years ago, when I began studying Eastern philosophy, I became intrigued with Philosophical Taoism, a Chinese philosophy which originated about 550 B.C.E., roughly the same time as Buddhism emerged in India. Central to Taoist philosophy is the concept of Yin and Yang or cosmic unity and balance, symbolized by the taijitu.

The taijitu diagram illustrates the principle that opposites are not separate, opposing forces, but mutually-dependent, mutually-defining poles of a single system. Each force exists only in relationship to its opposite, each is “completed” by its opposite, and each gains life and expression through the interplay with its opposite. This interrelationship is represented by the two halves of the diagram. The white creates and defines the black; the black creates and defines the white. Each figure can be perceived only against the background of the other. Take one away and the other ceases to exist

Hsiang sheng: “Dependent arising” or “inseparability”

The foundation of this interdependent nature of Yin and Yang is a relationship called hsiang sheng, which means “mutual arising,” “dependent arising,” or “inseparability” (Watts, 1977; Mair, 1990). Hsiang sheng tells us that one pole of a system (event, concept, etc.) cannot arise in isolation. Its complimentary pole must arise with it as the ground against which it is perceived. For example, when we perceive tallness, we must simultaneously perceive a background of shortness. We cannot create a goal without, at the same time, creating obstructions to that goal. Movement cannot exist except in relation to resistance or stillness. Inherent in a problem is its own solution. Focusing on good accentuates evil.

Though poles may appear as conflicting opposites, they are really connected. Their estrangement is an illusion created by our discriminating, categorizing intellects, which tend to attach us to the positive or pleasure-giving pole while repressing the negative or pain-producing pole. Thus, our discriminating mind creates the perception of polarity: “By the very act of focusing our attention on any one concept we create its opposite” (Capra, 1991 p. 145).

While the division or segregation created by discrimination is essential to survival in everyday life, it is not a fundamental reality of being (Capra, 1991). In fact, focusing excessively on one pole and ignoring its compliment can cause tension and imbalance in our lives. In the context of the journey, when the individual becomes fixated on her own life and understandings, she separates herself from the self-regulating relationship between herself and her world. Eventually, she is called on a journey to harmonize her understandings with those of her culture, restoring balance to the two poles of her existence.

Psychological Implications of Dependent Arising

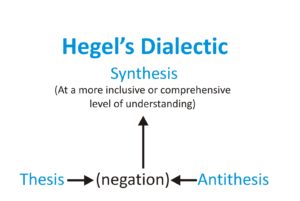

Hsiang sheng suggests interesting implications in psychology. For example, if we select from a whole experience (a gestalt) a single element that emphasizes what we like or acknowledge in ourselves, we must deselect (reject or repress) other elements of that experience that draw our attention to aspects of our personality we disown or reject. However, hsiang sheng tells us that the deselected experiences cannot just disappear. They are parts of the whole “who-I-am” system, the gestalt, and eventually, when the tension between the two poles of our self-perception is great enough, they will be synthesized, leading to growth and transformation.

Other psychological theories suggest this same transformational potential in opposites. Gestalt theory tells us that we perceive ourselves only against the ground of what we are not, so—paradoxically—what we are not is also a part of us and eventually it must be brought to awareness, articulated and harmonized. Repressing this recognition creates problems. In Jungian psychology, increasing the emphasis on positive aspects of our self causes a corresponding increase in the intensity of the balancing or Shadow aspects. In a healthy person, there is a dynamic tension and interplay between the ego and the shadow. When they work in harmony, psychic energy is freed, and the person feels energetic and unified (Hall & Nordby, 1973).

Buddhist philosophy, too, includes the concept that dependent arising is a key element in polar transformation. The Buddhist “Wheel of Life” (right), which is a metaphor for the different patterns of attachments that cause psychological problems, depicts six “realms.” Each realm contains two drawings, one symbolizing the nature of the problem inherent in that realm and the other a particular bodhisattva (enlightened teacher), representing the means for liberation from the problem.

…one of the most compelling things about the Buddhist view of suffering is the notion…that the causes of suffering are also the means of release; that is, the sufferer’s perspective determines whether a given realm is a vehicle for awakening or for bondage. …our faulty perceptions of the realms—not the realms themselves—cause suffering (Epstein, 1995, p. 16).

Figure and Ground: The Paradox of Being

This mutuality leads us to a second important characteristic of hsiang sheng: the principle of figure and ground. This principle illustrates our perceptual tendency to separate whole figures from their backgrounds. As a result, we when perceive an image, it stands out in contrast to its background, with everything that is not it. For example, a tall figure appears tall only in relation to a ground of shortness, and shortness is short only because of its relationship to tallness. Take away the ground and the figure disappears. Remove shortness, for example, and everyone is tall, which means everyone is average, so tallness disappears.

Because they are mutually arising, figure and ground exist interdependently, in dynamic relation to each other: “We are not aware of any figure — be it an image, sound, or tactile impression — except in relation to a background. . . . What we perceive is never a figure alone but a figure/ground relationship” (Watts, 1974, p. 19). Thus the nature of perception is to apprehend not just the figure, but the entire field or the figure-ground relationship. The relationship between the figure and the ground is the meaning. When we fight this natural process of perceiving the figure-ground relationships, we lose the creative tension that builds meaning in our lives. As Jung has said, “Meaninglessness inhibits fullness of life and is therefore equivalent to illness. Meaning makes a great many things endurable-perhaps everything” (1963, p. 340).

In Gestalt therapy, this interplay between the figure and ground is critical. “Gestalt therapy sees the viability of the self in the dynamic interplay of figure and ground” (Perls, et. al., p. 18). Our sense of self depends on maintaining the elasticity of the figure/ground relationship, and it is, in the Gestalt view, the process of growth and maturation (Perls, et. al, 1951/1976).

Synthesis: Creating new Meaning

This interplay between the polar aspects of the figure-ground system parallels the concept of synthesis as the process for growth and transformation. In terms of our discussion, figure and ground are polar aspects of one reality, and it is the synthesis of the two (perception of the figure-ground relationship) that stimulates the construction of meaning and the process of transformation.

This blockage in figure-ground relationship brings us again to the journey as a process of reconciling polar aspects of life. Often our call to adventure is the realization that we have attached ourselves to a “figure” in our life and lost sight of the “ground” from which it arises. When we ignore this relationship, we lose the ability to create meaning and purpose. By identifying with one aspect of our existence—our needs, our work, our fear—we throw our lives out of balance. The journey can be the process of restoring the field-ground relationship, releasing the dynamic energy that flows between those poles and restoring energy and meaning to life.

We can see the importance of understanding the figure-ground relationship in the context of adolescent behavior. If a child is belligerent in school, for example, initially we might believe that the belligerent attitude is the problem. However, when we were to look at the ground, the life from which that behavior arises, we might see that the belligerence is a survival tactic in an abusive or repressive home life. In other words, the figure and ground form the gestalt that is the basis of the child’s behavior. To help the child, we must address the figure (the behavior) with an understanding of its context in the ground (the child’s whole life).

Hsiang Sheng and the Hero’s Journey

In the context of the Hero’s Journey, the journey becomes the process of reconciling and synthesizing of this figure-ground relationship into a new perspective (a new level of consciousness). Often our Call to adventure is the awareness, perhaps subconsciously, that we have attached ourselves to a “figure” in our life and lost sight of the “ground” from which it arises. When we lose that greater perspective, we lose the ability to create meaning and purpose. By identifying with one aspect of our existence—our needs, our work, our fears—we throw our lives out of balance. The journey can be the process of restoring the field-ground relationship, releasing the dynamic energy that flows between those poles and restoring energy and meaning to life.

References

Capra, F. (1991). The Tao of Physics. Boston: Shambhala.

Capra, F. (1982). The turning point: Science, society and the rising culture. New York: Bantam.

Chen, E. (1989). The Tao Te Ching: A new translation with commentary. New York: Paragon House.

Coomaraswamy, A. K. (1943). Hinduism and Buddhism. New York: Philosophical Library.

Elkind, D. (1998). All grown up and no place to go: Teenagers in crisis (rev. ed.). New York, NY: Perseus.

Epstein, M. (1995). Thoughts without a thinker: Psychotherapy from a Buddhist perspective. New York: BasicBooks.

Feinstein, D. & S. Krippner. (1988). Personal mythology: The psychology of your evolving self. Los Angeles: Jeremy P. Tarcher.

Feinstein, D. & Krippner, S. (1997). The mythic path. New York: G. P. Putnam.

Feinstein, D. & Krippner, S. (1997). They mythic path. New York: G. P. Putnam.

Grondin, J. (1994). Introduction to philosophical hermeneutics. (J. Weinsheimer, Trans.). New Haven, CN: Yale University.

Freeman, Helen. (2002). Facing Fundamentalism. European Judaism. 35(1), 31.

Hall, C. S., & Nordby, V. J. (1973). A primer of Jungian psychology. New York: Penguin Books.

Jung, C. (1963). Memories, Dreams, Reflections. New York: Vintage.

Jung, C. (1976). “The Transcendent Function.” In J. Campbell (ed.), The Portable Jung (pp. 273-300). New York: Penguin.

Kelly, G. (1955/1963). A theory of peronality: The psychology of personal constructs. New York: W. W. Norton.

Kohler, W. (1947, 1975). Gestalt psychology: The definitive statement of the gestalt theory (1st ed.). New York: Liveright.

Mair, V. (1990). Tao Te Ching. New York: Bantam.

May, R. (1983). The discovery of being: Writings in existential psychology. New York: W. W. Norton.

May, R. (1991). The cry for myth. London: W.W. Norton and Company.

Mitchell, S. (1988). Tao Te Ching. New York: Harper & Row.

Moran, D. (2000). Introduction to Phenomenology. New York: Routledge.

Nairne, J. (2000). Psychology: The adaptive mind. Stamford, CT: Wadsworth

Novak, P. (1994). The world’s wisdom: Sacred texts of the world’s religions. San Francisco: Harper.

O’Brien, T. (1990). The things they carried. New York: Penguin.

Polkinghorne, D. E. (1988). Narrative knowing and the human sciences. Albany, NY: State University of New York.

Rosen, D. (1996). The Tao of Jung: The way of integrity (1st ed.). New York: Viking.

Silko, L. M. (1977). Ceremony. New York: Penguin Books.

Van Manen, M. (1990). Researching Lived Experience: Human science for an action sensitive pedagogy. New York: State University of New York.

Watts, A. (1973). The Tao of philosophy (audiotape). San Anselmo, CA: Electronic University.

Watts, A. (1974). The two hands of God: Myths of polarity. New York: Collier.

Watts, A. (1977). Tao: The watercourse way. New York: Pantheon.

Copyright © 2016 by Reg Harris. All rights reserved.